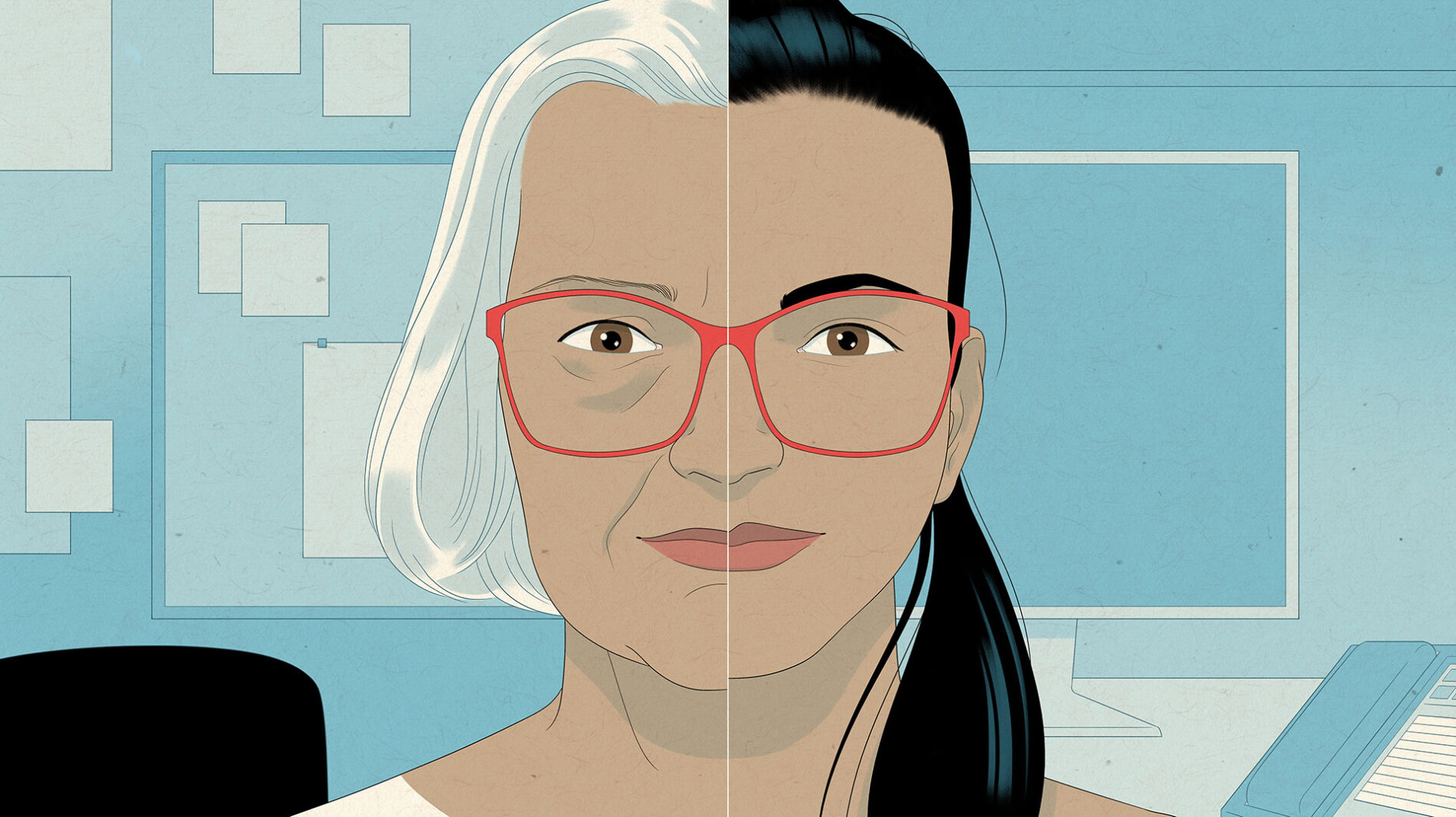

Harnessing the Power of Age Diversity

代际冲突现象由来已久。2019年年底,年轻人流行回嘴“好吧,婴儿潮一代的老家伙”,两代人针锋相对的广泛现象引起关注。

Conflict between generations is an age-old phenomenon. But at the end of 2019, when the retort “OK, Boomer” went viral, the vitriol — from both young people who said it and older people who opposed it — was pointed and widespread.

“好吧,婴儿潮一代的老家伙。”这句含讥带讽的话,是年轻一代用来应付他们觉得对自己居高临下指指点点很有优越感的老年人的。虽然“婴儿潮”一词在美国以外很少使用,但从韩国到新西兰都流行起了这句话。这句讥讽反映了不同世代在几乎所有问题上的巨大分歧:政治积极性、气候变化、社交媒体、技术、隐私、性别认同等。

The sarcastic phrase was coined by a younger generation to push back on an older one they saw as dismissive and condescending, and it became popular from Korea to New Zealand even though the term “Boomer” is barely used outside of the United States. The retort captured the yawning divide between the generations over seemingly every issue: political activism, climate change, social media, technology, privacy, gender identity.

美国第一次出现五代人同在职场(沉默一代、婴儿潮一代、X世代、千禧一代、Z世代),世界其他地区也有类似的情况,代际冲突正在升级。不同世代之间产生的愤怒和不信任,会限制合作、激发情绪性的冲突并导致员工流失率提升,从而影响团队表现。对年龄问题缺乏意识和理解,会在招聘和晋升中催生歧视,造成法律诉讼的风险。

With five generations together in U.S. workplaces for the first time (Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z), and similar dynamics playing out in other parts of the world, tensions are mounting. The anger and lack of trust they can cause hurt team performance by limiting collaboration, sparking emotional conflict, and leading to higher employee turnover and lower team performance. And a lack of awareness and understanding of age issues can drive discrimination in hiring and promotion, leading to lawsuit risks.

然而许多组织并未针对代际问题采取措施。前不久企业更新了多样性方面的方案,只有8%的组织将年龄纳入多样性、公平及包容战略的考量。而这些组织的策略往往也只是鼓励不同世代的人关注彼此的相似之处,抑或根本不承认不同世代之间现实存在的差异。

But many organizations don’t take steps to address generational issues. While companies have recently renewed their diversity efforts, only 8% of organizations include age as part of their DEI strategy. And of organizations that do address it, the strategy has often been to simply encourage those of different generations to focus on their similarities or to deny the reality of their differences altogether.

这样会错失机遇。年龄多样化的团队之所以有价值,是因为将能力、技能、信息和人际网络互补的人聚集到一起。倘若管理得当,年龄多样化能够提升决策质量、合作效率和团队整体表现,但前提条件是团队成员愿意分享,并从彼此的差异中学习。试想一支由各年龄层的产品开发者组成的团队,将年长成员的丰富经验、广阔客户网络和年轻成员的新颖视角与最新供应商网络结合起来——这样的团队可以运用年龄多样性,建立起仅靠单独某个年龄层成员无法实现的优势。

This is a missed opportunity. Age-diverse teams are valuable because they bring together people with complementary abilities, skills, information, and networks. If managed effectively, they can offer better decision-making, more-productive collaboration, and improved overall performance — but only if members are willing to share and learn from their differences. Think of a multigenerational team of product developers, merging the seasoned experience and broad client network of its older members with the fresh perspectives and up-to-date supplier network of its younger ones. Such a group can use its age diversity to build something no generation could on its own.

例如密歇根理工大学的开放可持续技术实验室,这支跨世代团队开发出了第一台低成本开源金属3D打印机。实验室前任主管乔舒亚·皮尔斯(Joshua Pearce)把团队的成功归功于成员愿意向其他年龄层的队友学习。为了开发新产品,团队需要X世代教职员工的技术能力、千禧一代研究生的软件才能和婴儿潮一代研究人员的经验智慧。比如一位年轻成员要从亚马逊订购急需的机械零件,年长的队友会介入,用备件组装出需要的零件,比亚马逊配送还快。团队结合各年龄层成员不同的能力,以比以往低得多的成本实现了铝材和钢材3D打印。

Take the Open Sustainability Technology Lab at Michigan Technological University, a multigenerational team that developed the first low-cost open-source metal 3D printer. Former director Joshua Pearce credits the team’s success to members’ willingness to learn from those of other generations. To develop their new product, they needed the technical skills of Gen X faculty, the software wizardry of Millennial graduate students, and the experienced resourcefulness of Boomer researchers. For example, once when a younger team member turned to Amazon to order an urgently needed mechanical component, an older colleague intervened and built it from spare parts more quickly than even Amazon could have delivered it. By combining abilities, the team developed the ability to 3D print in aluminum and steel at a much lower cost than had been possible.

这正是代际差异不宜掩盖的原因。我们与金融、医疗、运动、农业和研发等各领域的年龄多样化团队合作,发现更好的方法是帮助人们认识、欣赏和利用自己与其他年龄层的差异,即组织处理其他多样性的方式。证据表明,运用经过实践检验的多样性、公平及包容工具弥合代沟,可以减少冲突和刻板印象,改善员工的组织归属感、工作满意度、流失率和组织绩效。

That’s why papering over generational differences isn’t the answer. Through our work with age-diverse groups in finance, health care, sports, agriculture, and R&D, we’ve found that a better approach is to help people acknowledge, appreciate, and make use of their differences — just as organizations do with other kinds of diversity. Evidence shows that when time-tested DEI tools are used to bridge age divides, they can reduce conflict and generational stereotypes and improve organizational commitment, job satisfaction, employee turnover, and organizational performance.

我们在《代际情商》(Gentelligence)一书中提出一套框架,引导员工远离代际冲突、以更有效的方式接受彼此之间的差异。框架共有四个步骤,前两步是识别自己的预设、调整自己的滤镜,克服错误的刻板印象,后两步则是利用差异、促进相互学习,指导员工分享知识、共同成长。每一步都有一项实践活动。有代际冲突问题的团队应当从前两步开始纠正问题。后两步则是帮助团队在和睦相处的基础上更进一步,实现跨年代团队特有的学习和创新。

In our book, Gentelligence, we lay out our framework for moving colleagues away from generational conflict and toward a productive embrace of one another’s differences. There are four practices involved. The first two, identify your assumptions and adjust your lens, help overcome false stereotypes. The next two, take advantage of differences and embrace mutual learning, guide people to share knowledge and expertise so that they can grow together. Each practice also includes an activity to apply its ideas. Teams experiencing generational conflict should start with the first two; the latter two will help groups move beyond simply getting along and leverage the learning and innovation that intergenerational teams can offer.

为了介绍这套框架,首先来看看“一代人”的定义要素和代际差异的由来。

To introduce the framework, let’s look at what makes a generation — and what makes generations different from each other.

如今的世代

Generations Today

一代人是指在同一历史时期出生、因此在相似的人生阶段经历了特定重大事件的年龄群体。这些共同经历,如高失业率、人口激增、政治变动等等,都会以独特的方式塑造这一群体的价值观和行为标准。不同文化中这种塑造性的体验各自迥异,所以世界各地不同世代的具体特征各不相同。

A generation is an age cohort whose members are born during the same period in history and who thus experience significant events and phenomena at similar life stages. These collective experiences — say, high unemployment, a population boom, or political change — can shape the group’s values and norms in a unique way. Because these formative experiences vary from culture to culture, the specifics of generational makeup vary around the world.

但在全球范围内,几代人之间彼此不同的眼界、态度和行为都会引起冲突。例如在许多国家,数十年来一直在工作场所占主导地位的年长员工因为健康状况改善、寿命增加,占据高位的时间更长了,年轻员工急于向上流动,往往等不及他们让位。婴儿潮一代和数字原住民一代一起工作,可能会就“谁的贡献更有价值”发生矛盾。如果一位年长员工开发的客户数据库被年轻同事建议的自动化软件所取代,年长员工会觉得自己的贡献受到了轻视。

But across geographies, the different outlooks, attitudes, and behaviors of cohorts can lead to conflict. For example, in many countries older workers, who have dominated the workplace for decades, are staying in it longer due to better health and longevity. Younger colleagues, anxious for change and upward mobility, are often impatient for them to move on. And when Boomers and digital natives work side by side, tensions can arise about whose contributions are valued more. If the client database that an older employee developed is replaced by automated software suggested by a younger associate, the older employee may feel that their contribution is being minimized.

瘟疫流行之下,代际问题更加明显。大辞职时期有各个年龄层的员工辞职,于是年长者和年轻者开始竞争相似的职位。虽然年长员工更有经验,最近针对招聘经理的一项问卷调查表明,他们认为35岁以下年龄群体的教育背景、技能和文化背景最适合目前空缺的职位。新冠疫情流行期间,所有人都上网,但不同世代选择的平台也不同——年长者刷Facebook,年轻人刷TikTok,使得数字代沟进一步加深。而Z世代员工迄今的职业生涯大部分乃至全部是远程工作,很多人感到与同事缺乏联系,且被年长同事轻视。年长员工适应居家办公的情况则好于预期,在办公室加了一辈子的班,发现灵活办公让人精神百倍。

These generational frustrations have become even more pronounced during the pandemic. As people of all ages have left their jobs in the so-called Great Resignation, older and younger workers are competing for similar roles. While older workers have more experience, the 35-and-under age groups, according to a recent survey of hiring managers, are seen as having the most relevant education and skills and the best cultural fit for open positions. Even as people flocked online during the pandemic, different generations tended to spend time on different platforms — older people scrolling Facebook, younger ones TikTok — deepening the digital divide. Gen Z employees, meanwhile, have worked remotely for most if not all of their professional lives, leaving many feeling disconnected from coworkers and undervalued by their older teammates. And older generations have adjusted to working from home better than expected, finding the flexibility energizing after a lifetime of long hours at the office.

这些矛盾和相关的媒体炒作,进一步影响了代际信任。以下四项实践活动就是为了弥合代沟、推动更好的跨世代合作而设计的。

Many of these tensions — and the media hype around them — have led to a further decline in trust between the generations. The steps we outline in the four practices and activities below are designed to help bridge that gap and move toward better intergenerational cooperation.

识别自己的预设

Identify Your Assumptions

我们对各年龄群体(包括自己所在的年龄群体)的预设会阻碍我们了解队友的真实自我以及他们要提供的技能、信息和社会联系。意识到自己抱有预设,是克服预设的第一步。

The assumptions we make about generational groups (including our own) can hold us back from understanding teammates’ true selves as well as the skills, information, and connections they have to offer. Noticing that we’re making these assumptions is the first step to combating them.

比如2019年的头条新闻:“为何‘懒惰’‘狂妄’的千禧一代一份工作坚持不了90天”。像往常一样,这种公开的刻板印象经不住仔细审视。皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)发现,目前处在26岁至41岁之间的千禧一代为一个雇主效力13个月以上的比例为70%,X世代在同一人生阶段能坚持这么长时间的比例为69%。

Take headlines such as this one from 2019: “Why ‘lazy,’ ‘entitled’ millennials can’t last 90 days at work.” As is often the case, the stereotype on display falls apart on closer inspection. Pew Research Center has found that 70% of Millennials, who are currently aged 26 to 41, stick with their employers for at least 13 months; 69% of Gen Xers stayed that long during the same period of their lives.

不是所有偏见都明目张胆到能上头条。但即使是潜意识的观念也会影响我们的互动和决策,自己通常意识不到。试想你被要求推荐几位队友主导在Instagram上的宣传活动,你会想到哪些人?大概就是那些二十几岁的同事。表面上你觉得自己选择了最合适、最有兴趣且最有能力从这个任务中获益的人,但你或许下意识地依赖根深蒂固的预设——年长者不喜欢科技,或者没有兴趣学习新事物。

Not all biases are blatant enough to make headlines. But even beliefs that we hold at the subconscious level can influence our interactions and our decision-making, often without us realizing it. For example, imagine being asked to nominate a few teammates to lead an Instagram campaign. Who comes to mind? Probably some of your 20-something colleagues. Consciously, you may believe you are choosing those who are the most qualified, most interested, and most able to benefit from the experience. Unconsciously, you may be falling back on deeply embedded assumptions that older people dislike technology or are uninterested in learning anything new.

谈到跨年龄团队的冲突,人们通常觉得跟年龄有关,这个方向是对的,但具体的猜想往往有偏差。来看我们研究中的具体例子。加利福尼亚大学伯克利分校Fung Fellowship的领导者让本科生和退休人员组成团队,合作开发老年人健康产品。团队最初碰上了若干人际难题,例如退休人员没能迅速回复年轻队友发来的短信,学生们觉得这些人没有认真对待自己或项目。而退休人员则对他们的预设和似乎杂乱无章的沟通方式感到气愤。双方关系变得紧张,影响了工作进展。

When it comes to conflict on intergenerational teams, people often rightly suspect there’s something age-related going on, but they frequently assume it means something other than what it really does. Let’s look at how this played out on one team we studied. At the Fung Fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley, leaders created teams of undergraduates and retirees to collaborate on wellness products for older adults. Initially, these teams ran into several interpersonal challenges. For example, when the retirees didn’t respond quickly to texts sent by their younger peers, the students felt that their counterparts weren’t taking them or the project seriously. Meanwhile, the retirees resented their teammates’ assumptions and seemingly haphazard communication. Work slowed as relations became strained.

这样的团队需要运用工具找到自己抱有的年龄偏见,理解人际关系中存在的矛盾,消除正在酝酿的冲突。我们推荐预设审查法。

Such teams need a tool to recognize the specific age biases they may hold, understand tensions that exist, and head off brewing conflict. We recommend an assumption audit.

让员工在一周时间里对日常工作中基于年龄的预设保持高度警惕,关注自己和他人的行为。你可能会注意到某位团队领导者驳回了年轻员工想承担更大责任的要求、认为这是不知天高地厚,或者是你自己将年长员工排除在创新会议之外。

Challenge employees to spend a week on high alert for age-based assumptions in their daily work. Have them pay attention to their own actions as well as others’. This might mean noticing, for example, that a team leader dismissed a young employee’s request for more responsibility as “entitled” behavior or that you left senior employees out of your meeting on innovation.

一周过后,安排时间与团队讨论,让每个人提出至少一条自己的所见所感。这样的讨论可能会激起抵触和防卫,但明确基本规则可以有效地避免这种结果。指导员工讲述自己的见闻,不要预设意图:“年轻成员的意见被迅速驳回”,不要擅自解读为“年长领导者驳回年轻成员的意见,因为觉得年轻人什么都不懂”。鼓励每个人接受反馈,思考基于年龄的预设(无论有无道理)对团队凝聚力、敬业度和表现的影响。

After the week has passed, schedule time with the group to discuss their experiences, asking each person to bring at least one observation to the table. These conversations can get charged or lead to defensiveness, but clear ground rules can go a long way in preventing those outcomes. Instruct people to speak about what they heard and saw but not to assume intent: “Input from our younger teammates is dismissed quickly” rather than “Senior leaders dismiss our younger teammates’ input because they don’t think they have anything to offer.” Encourage everyone to be open to feedback and to consider how age-based assumptions — whether containing some truth or absolutely false — might be affecting team cohesion, engagement, and performance.

计划在几周后安排后续会议,继续讨论,确保问责,并开始在日常工作中增强相关意识。

Plan a follow-up meeting for several weeks later to continue the conversation, ensure accountability, and start building awareness into your everyday work.

Fung Fellowship项目领导者开展了预设审查,寻找大学生和退休人员组成的跨年龄团队工作进展不顺利的原因。他们发现,年轻的团队成员预设,对方应该知道在工作时间以外发送的短信肯定很紧急、要迅速回复,而年长成员则理所当然地认为短信可以等到第二天早晨再说。明确这些预设,促使团队就沟通制定了统一的规范。

When the Fung Fellowship program leaders did their own assumption audit to uncover why the undergraduate-retiree teams were struggling, they found that younger team members had assumed that texts sent after hours would be deemed urgent and would get a quick reply. But older peers thought it went without saying that a text could wait until morning. Identifying these assumptions prompted the team to set shared norms around communication.

调整自己的视角

Adjust Your Lens

察觉预设很重要,但团队还需要战胜预设。刻板印象往往使得我们将差异错误地归因于年龄,或者预设子虚乌有的恶意。调整自己的视角,要思考自己察觉到的预设是否符合当前的现实状况,是否仅凭自己的参照系评判他人的行为和态度。试着理解为何不同年龄层的同事会有与你不同的行为,拓宽自己的思维,运用描述——解读——评价的方法。

Recognizing assumptions is important, but teams also need to combat them. Stereotypes often cause us to incorrectly attribute differences to age or to assume ill intent where there is none. Adjusting your lens means considering whether the assumptions that you’ve identified align with the reality of the situation at hand, or whether you’ve been judging someone’s actions and attitudes based only on your frame of reference. Try to understand why colleagues from different generations might behave differently than you do. To expand your thinking in that way, use the describe-interpret-evaluate exercise.

这套方法出现于1970年,当时是为了协助海外赴任的员工,也可以帮助跨年龄层团队的成员拓宽对彼此的了解。

Developed in the 1970s to prepare employees to work abroad, this exercise can also help members of age-diverse teams broaden their understanding of one another.

首先,让每一名员工描述自己与不同年龄层的人相处遭受的一次挫折。其次,请员工思考自己最初对于对方行为的解读。最后要求他们再想出另一种不同的解释,也可以请其他团队成员贡献意见。

First, have each employee describe a frustration they have with someone of a different generation. Next, ask them to think about their initial interpretation of the person’s behavior. Finally, challenge them to come up with an alternative evaluation of your interpretation; they can also ask for contributions from the group.

例如前不久本文作者梅甘为一个医疗专业团队开办研讨会。一位把自己定位为婴儿潮一代的护士长说,年轻患者在与护士或医生谈话时使用手机,令她烦恼。她对这种行为的解读是年轻患者没有礼貌,对照护团队心不在焉。要求她想出另一种解释的时候,她露出困惑的表情,什么都想不出来。不过其他同事(大部分是年轻些的医生和护士)提出了很多想法:年轻患者可能是在记录对话要点,或是在查药房营业时间、以便在关门前拿到药。听了队友的观点,护士长的表述有所改变。她得以从不同的角度看待患者的行为,更加了解患者的视角。与此同时,年轻同事也明白了,自己觉得自然而然的行为,比如在谈话中看看手机,可能会冒犯年长同事。

For example, recently one of us (Megan) conducted a workshop with a group of health care professionals. A nursing manager who identified herself as a Baby Boomer described being annoyed with young patients who used their mobile phones in the middle of a conversation with a nurse or a doctor. Her interpretation was that the patients were — rudely — not paying attention to their caregiving team. When prompted to think of alternative explanations, she looked confused, unable to come up with anything. But her colleagues — mostly younger doctors and nurses — had plenty of ideas: The young patients might be taking notes on the conversation or looking up the pharmacy’s hours to make sure they could get their prescriptions before closing. As her teammates offered these insights, the nursing manager’s expression changed. She was able to see the behavior in a different light and better appreciate the patients’ perspectives. At the same time, her younger colleagues realized how behavior that felt natural to them — like checking a phone mid-conversation — might offend older peers.

利用差异

Take Advantage of Differences

通过意识到自己的预设并调整视角的方式缓和了代际矛盾,就可以与其他年龄层的同事一起寻找有益的差异,设法从彼此的观点、知识和人脉中获益。

Once you’ve tempered generational tensions by recognizing assumptions and adjusting lenses, you can work on finding productive differences with your colleagues of other generations and ways to benefit from each other’s perspectives, knowledge, and networks.

哈佛商学院埃米·埃德蒙森(Amy Edmondson)的研究表明,团队成员需要有一定程度的心理安全感,才能轻松自如地提出新创意或有争议的信息。但正如我们所见,人们在工作场所感受到的代际竞争已经损害了信赖关系,一味追求流量的新闻更是推波助澜。重建信赖的一种好方法是召开圆桌会议,承认和重视团队的多样化视角。

For team members to feel comfortable sharing in this way — bringing up new ideas or conflicting information — they need to feel a certain amount psychological safety, as the research of Harvard Business School’s Amy Edmondson shows. But, as we’ve seen, perceived generational competition in the workplace, exacerbated by clickbait headlines, has undermined trust. One good way to rebuild it is to hold a roundtable where the team’s diverse perspectives can be acknowledged and valued.

跨年龄团队的领导者应当在每月或每季度安排会议,鼓励员工贡献提升合作效率、改善工作关系的创意。这个过程分为两个阶段:

Leaders of intergenerational teams should set monthly or quarterly meetings to elicit ideas for how to work together more productively and smoothly. There are two stages to the process:

一、寻找相似和共通之处。目标分明是利用差异,关注共同点似乎有些奇怪,但团队成员首先必须将彼此视为某项共同任务的合作共事者,而非竞争者。此外,研究表明,共同的宗旨和目标对于团队表现至关重要。跨年龄团队可能比其他类型的团队更难找到共通的地方。因此要在第一次圆桌会议上让团队成员一起回答一些问题,如“这个团队为何而存在?”“我们希望达成怎样的共同目标?”这样有助于团队成员感到彼此是追求共同利益的联盟,建立心理安全感。在之后的圆桌会议中,要提醒他们想起此时的讨论。

一、Find common ground and similarities. While it may seem counterintuitive to focus on commonalities when the goal is to leverage differences, team members must first see themselves as collaborators on a joint mission, rather than competitors. Furthermore, research shows that having a common purpose and goals are vital to team performance. Intergenerational teams can struggle more than most to find that shared ground. So at your first roundtable, ask teammates to work together to answer questions such as “Why does the team exist?” and “What shared goals do we want to accomplish?” This helps team members begin to see themselves as unified in pursuit of the same interests and builds psychological safety. At future sessions, remind them of these discussions.

二、征集独特观点。找到共同点之后,让每一位团队成员回答下列问题:

- 我们作为一个团队在实现共同目标的过程中哪些地方做得好?

- 哪些行为阻碍我们实现目标?

- 有哪些应当充分利用的机会是我们目前尚未把握的?

- 如果你是管理者,你会继续哪些行为,停止或开始哪些行为?

二、Invite unique viewpoints. Next, have each team member respond to the following questions:

- What are we, as a team, doing well to accomplish these shared goals?

- What are we doing that is keeping us from reaching these goals?

- What opportunities should we take advantage of that we currently aren’t?

- If you were in charge, what would you continue, stop, or start doing?

你的目的不是得出简洁的结论,而是发掘过去可能被驳回或未能表达的新观点。不同的观点必然会出现,也有可能爆发冲突,没关系,只要不断把对话引回到团队共同目标上,强调不同的观点都是对实现共同目标的重要贡献。

Your aim is not to come to neat conclusions but to surface new ideas that might have been dismissed or unvoiced in the past. Different views will inevitably surface, and some conflict may even erupt — that’s all right. Just keep bringing the conversation back to the team’s shared goals and emphasize that differences of opinion are valued contributions toward your common success.

我们采访过的富国银行客服经理兼副总裁亚伦·霍恩布鲁克(Aaron Hornbrook),每月为自己管理的跨年龄团队召开圆桌会议。每场会议开始时,霍恩布鲁克都会提醒大家,团队的宗旨是帮助客户解答关于申请和账户的问题,履行这一宗旨需要有意愿倾听所有团队的观点并且彼此信赖。他的努力已经有了成果:例如,团队里的千禧一代和Z世代员工能够放心地吐露对于心理健康的忧虑——以往一些年长同事认为这个话题是禁忌。这样的对话帮助霍恩布鲁克和其他高管同事明白了为何最近申请带薪休假的人数激增,并促使他们设法帮助员工缓解焦虑,如要求主管在大会议室而非办公桌边与下属单独谈话。如此一来,各个年龄层的团队成员都开始为维护心理健康而带薪休假的同伴提供更多支持。

Aaron Hornbrook, a customer service manager and vice president at Wells Fargo we’ve interviewed, holds monthly roundtable meetings with his multigenerational team. At the beginning of each, Hornbrook reminds everyone that their mission is to help customers with their application- and account-related questions and that success will require both trust and willingness to listen to the perspectives of the entire group. His efforts have borne fruit: For example, his Millennial and Gen Z employees feel comfortable voicing their concerns about mental health in the workplace — a subject previously considered taboo by some of their older colleagues. These conversations helped Hornbrook and other senior colleagues understand why paid-time-off requests had spiked recently and prompted them to find ways to reduce employee anxiety, including by requiring supervisors to hold one-on-one meetings with direct reports in conference rooms rather than at their desks. As a result, team members of all generations became more supportive of people taking mental health days.

管理者为团队成员提供讨论团队运作情况的空间,表明所有观点都能得到重视。

By creating a space for team members to discuss how the group functions, managers demonstrate that all perspectives are valued.

互相学习

Embrace Mutual Learning

要想充分发挥跨年龄团队的益处,必须让团队成员相信自己能从不同年龄段的同事身上有所收获。最终目标的相互学习:各个年龄层的同伴教学相长,不断循环。

Finally, to fully reap the benefits of intergenerational teams, members must believe that they have something to learn from colleagues in different age cohorts. The ultimate goal is mutual learning: peers of all ages teaching and learning from one another in an ongoing loop.

鼓励教学相长的一种方法是提供正式辅导项目,很多组织都有让老员工带新员工的传统辅导项目,不过通用电气、德勤、普华永道、思科和宝洁等一些顶尖公司建立了“反向辅导”项目,让年轻员工向老员工传授新技能,特别是技术方面的技能。我们建议企业乃至小团队管理者将这两种方法合二为一,实现“相互辅导”。研究表明,相互辅导项目可以支持员工发展新能力,并增加个人参与度和集体动力。

One way to encourage this is with formal mentoring initiatives. While traditional mentoring programs (older colleagues teaching younger ones) exist at many organizations, a number of top companies — including GE, Deloitte, PwC, Cisco, and Procter & Gamble — have developed “reverse mentoring” programs, where younger people teach older peers new skills, typically around technology. We suggest that companies and even managers of small teams combine both approaches into two-way “mutual mentoring.” Research shows that such programs support employees’ development of competencies and skills and increase both individual involvement and collective motivation.

不同年龄层的员工建立起良好的关系,一同留意寻找机会时,也会自然地开始相互学习。我们研究过的数字化叙述公司BuildWitt Media,协助建筑业和采矿业的客户吸引优秀人才。公司创始人兼CEO亚伦·威特(Aaron Witt)26岁,总裁丹·布里斯科埃(Dan Briscoe)53岁。跨年龄学习并不是他们合作的明确理由,但他们成功地将布里斯科埃30年的领导、销售和营销经验与威特的冲劲、对商业趋势的感知和移动媒体原住民的优势结合到一起。举例来说,布里斯科埃称威特教会自己在招聘时不只重视学历和成绩,并且在相应职位的职责范围以外考虑求职者是否具有领导潜力、文化及价值观是否适合公司。威特则表示布里斯科埃擅长与客户建立关系、促成交易。他们都同意这段合作关系促成了公司的快速成长,并带来了实现服务多样化的机会。

Mutual learning can also happen organically when people of different generations have good relationships and are on the lookout for opportunities. BuildWitt Media, a digital storytelling firm we’ve studied, helps its clients in the construction and mining industries attract great talent. Its founder and CEO is 26-year-old Aaron Witt; its president, Dan Briscoe, is 53. While cross-generational learning was never an explicit reason for their partnership, they have come to value how Briscoe’s 30 years of experience in leadership, sales, and marketing complement Witt’s impulsive energy, sense of business trends, and lifelong immersion in mobile media. For example, Briscoe credits Witt with teaching him to look beyond academic degrees and GPA when hiring and to consider leadership potential and alignment with culture and values in addition to a work portfolio. Witt says Briscoe is good at relating to clients and putting deals together. This partnership, they agree, has led to rapid growth and the opportunity to diversify their services.

若想在团队中建立辅导文化,首先要打造非正式的相互辅导网络。询问各年龄层的团队成员想学什么、想教什么。成员可能非常害羞,不肯标榜自己的专业技能,因此团队领导者可以提出建议,指出自己看到的他们的强项。

To start building a mentorship culture on your team, create an informal mutual mentoring network. Begin by asking team members of all ages what they want to learn and what they want to teach. Potential teachers can be surprisingly shy when it comes to their expertise; it may help if you make suggestions about what you see as their strengths.

找到天然存在的连接点:能玩转TikTok的员工和希望学习如何给自己拍小视频的员工,已经有了成熟的客户名册的员工和希望扩展人际网络的员工。这样的两个人不一定有年龄差距,要确保学习者和辅导者两个群体都涵盖所有年龄层。

Identify where there are natural connections: employees who are versed in TikTok and those who want to learn to create selfie videos, or employees who have an established roster of clients and those who want to expand their networks. While not all pairings need to be cross-generational, make sure all generations are represented in both the learner and the instructor groups.

让需求和技能正好匹配的员工两两组队之后,为整个团队开一次启动会议,请四到六名辅导者简单地介绍一下自己的专业领域。鼓励大家去找具备自己想学的技能的辅导者。启动会议本身就足以促成一些人组队,但领导者也要每个月提醒一次,让团队成员保持提问和学习。

Once you have some pairings ready, hold a kickoff meeting with the entire team and ask four to six mentors to present briefly on their area of expertise. Encourage people to reach out to the mentors whose skills they want to learn. Often the energy of the meeting itself will spur connections, but you can also send monthly nudges to remind the team to keep questions flowing.

即使是这种非正式的网络,也有助于建立跨年龄学习的文化。

Even this kind of informal network can help to build a culture of cross-generational learning.

• • •

“好吧,婴儿潮一代的老家伙”“玩世不恭的X世代”“狂妄的千禧一代”“雪花般脆弱的Z世代”……这些形容不同年龄层的称呼在我们心中根深蒂固——或者正好相反,我们以这种方式轻视实际存在的代际差异——于是我们忘记了年龄多样性的力量。特别是现在,工作方式发生了诸多变化,令我们应接不暇,领导者有责任重视跨年龄团队,把年龄作为多样性、公平和包容问题中的一个关键,而且要当作可把握的机遇,而非要掌控的威胁。

“OK, Boomer,” “Gen X cynics,” “entitled Millennials,” and “Gen Z snowflakes.” We have become so entrenched in generational name-calling — or, conversely, so focused on downplaying the differences that do exist — that we have forgotten there is strength in age diversity. Especially at a time when we are wrestling with so many changes to the way we work, it’s incumbent on leaders to embrace intergenerational teams as a key piece of the DEI puzzle and to frame them as an opportunity to be seized rather than a threat to be managed.

梅甘·格哈特是迈阿密大学法莫商学院管理学教授、领导力发展项目负责人,

威廉·艾萨克及迈克尔·奥克斯利商业领导力中心罗伯特·约翰逊教席联合负责人,《代际情商:领导跨年龄团队的全新方法》(Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce)作者之一。

约瑟芬·纳克姆松-埃克沃尔是花旗独立合规与风险管理副总裁,《代际情商:领导跨年龄团队的全新方法》作者之一。布兰登·福格尔是内布拉斯加大学林肯分校博士生,《代际情商:领导跨年龄团队的全新方法》作者之一。